There was some weakness on the exam answers, mostly on the background for thinking about false positives and false negatives. I’m going to start at the beginning and walk you through it.

First, there has to be some thing we’re measuring. In macro, this is most often real GDP. I’ve written in a bunch of other places (like the handbook, and this semester’s quodlibet) why we measure real GDP.

Second, we need to have some reason for forecasting that series. If we know it’s value in the future, there’s no need to forecast other than curiosity. The adjective we use for knowing a series’ future values is deterministic. Parts of real GDP might be deterministic, but the whole thing is not, so we want to forecast it. Alternatively, if no forecast is very good, then we might give up. GDP isn’t too hard to forecast, but it’s hard to forecast well: not because it requires a lot of skill, but rather just because it's fairly unpredictable (that's part of the reason no one believes the numbers coming out of China — they're too predictable to be real).

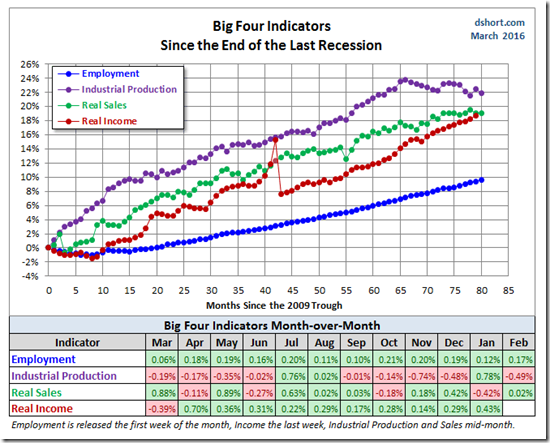

Third, fitting is a little different than forecasting. With both, we’re trying to predict one thing (that we can’t figure out well) from something else. With fitting, we’re using a variable we have right now to predict values for the thing we can’t figure out either at the same time or in the past. This is what we do with a coincident indicator like industrial production: we get new values of it first and we use them to fit what we think real GDP is going to be before we actually get its measurements. Forecasting is doing something similar, but now we’re trying to use a variable we have now to figure out some other variable we don't have yet. This is what we use leading indicators for.

Fourth, testing is a little different from forecasting. When we test for something, we’re looking for a yes or no answer. This is usually along the lines of asking if this thing is different than these other things. And that difference has to be worthwhile or we wouldn’t bother doing the test. In macroeconomics, we’re interested in whether we continue to be in an expansion (or have switched) or continue to be in a contraction (or have switched).

Note that it’s one thing (forecasting) to say that you have data on a leading indicator, and you expect it to be able to help explain the future behavior of a variable you’re interested in. But, it’s another thing (testing) to say that if your indicator has peaked, does that mean the variable you’re really interested in will peak too.

We do a lot of this very naturally when we care for a sick child at home. The first thing we’re interested in is the well-being of the child. The second thing is that we have some reason to forecast how the child feels, because this can tell us about their well-being. Third, we have coincident and leading indicators for well-being, like how much the child eats and does the child have sniffles. And fourth, sometimes we do a test to assess how the child is doing, by taking their temperature: most people will keep a child home from school if they have a fever even if they say they feel OK.

There’s an interesting notion here that you may not have thought about before: no one knows what temperature you should be when you’re sick! What we know is the temperature you should be when you’re

not sick.

When we put the implication of that in words it sounds confusing: we test whether you’re sick by assessing whether you’re not sick. When taking a child’s temperature, it’s either right, or it’s not. When it’s not, we declare that the child is sick.

Statisticians are pretty careful about the language they use for this. Most people aren’t very good at following their lead.

At home, we might say to ourselves that a child seems sick. It sounds technical, but some might say that we’re hypothesizing that the child is sick. So we take their temperature.

A statistician will be careful to state a null hypothesis and an alternative hypothesis. A test differentiates between those two. What’s important about choosing a null hypothesis is not that it be true (we may never know that) or even plausible. Instead, what’s important is that we know how the data will behave

if it is true.

In the case of a child, sometimes we may never really know for sure whether they are sick or not. But, whether we know that or not, we know that when they are

not sick their temperature will be around 98.6° F.

So the null hypothesis is that the child is

not sick, and the alternative is that they are sick. We take their temperature, and if it is close to 98.6° F we don’t reject the null hypothesis that the child is

not sick. If their temperature is far enough away from 98.6° F we reject the null that the child is

not sick.

I put all those "nots" in italics for a reason. Since we’re testing the null that they’re

not sick, it’s called a negative if we can’t reject it. If we can reject then it’s called a positive.

But is the negative or positive correct? We may never know. We don’t usually use the modifiers for true, but we do use them for false, and I’ll use both here to make a point. So, our test might deliver a negative to us, but we have to figure out whether it’s a (true) negative or a false negative: either the child is not sick or they have some illness which doesn’t cause fever . Alternatively, the test might deliver a positive to us, but we have to figure out whether it’s a (true) positive or a false positive: either we reject the null that the child is not sick or their temperature is off for some other reason.

Now I’m ready to add the fifth thing we need: an ability to explain how the data is going to behave if the null hypothesis is true (whether or not we can ever know that for sure). We take kid's temperatures because there's a fair presumption that if the kid is OK their temperature will be normal.

OK, are you with me? Let’s work backwards through what I just explained. If you get a false positive or false negative, it’s only because you did a test. But you’d only do the test if you can explain how the data will behave if some particular thing is true. And the test is only worthwhile if something is different that can be differentiated by it. Ideally this helps you make forecasts about a variable you’re interested in, and maybe that helps you figure out something even more important. One more thing: you're doing tests all the time whether or not you think about them that way (just like parents who listen for sniffles and coughs around the house) ... but your thinking about those tests may be clearer once you realize they're all around you.

What were some of the exam answers that motivated me to do this post then?

Some students just confused getting a positive or negative from a test, with data being positively or negatively correlated. Industrial production is negatively correlated with the unemployment rate, and it does lead it so it might form a good basis for a test. But if industrial production fell, and unemployment rose, I'd call that a positive (result from my test) because it's probably not dumb luck that I found something.

Some students said false positive and false negatives are just errors. They're actually much more than that, because we've chosen to do the test, and we never would have gotten to the error if we hadn't taken that action.

Further, those errors are always in relation to a null hypothesis, so you have to know what that was to figure out what could go wrong. Sending a sick kid to school is unfortunate, but it's not an error unless you took their temperature, found out it was normal, and acted on that.

False positives and negatives are also not just a matter of incorrectly reporting of something that should be obvious; instead they're mistakes we make about interpreting something that's murky to begin with. But they're really not even a misinterpretation: we'd be better off acknowledging that mistakes are going to be made even when we do everything right. Caregivers aren't always sure how sick kids are, and kids fake being sick too.

It's also not enough for the data to, say, go up and then down. You have to be thinking about actually doing something with those movements. You're probably not a good caregiver if you keep taking a child's temperature and then not doing anything with the information when you see they're running a fever.

Finally, while it can be about symptoms you've already observed, the point of doing the test is that you usually haven't observed them yet. In my house I used to drive my wife crazy when my kids were sick: I didn't bug them to much with the thermometer if it was already clear to me they were pretty sick — I'd just be bugging them, and it wouldn't tell me much I didn't know already. This is why hospitals take patients temperatures continuously in many cases, and do almost nothing with that information most of the time. They monitor it as a matter or routine, but it's just one component of what they do.

A lot of this probably seems like common sense. It is; I'm just being specific about the wording and the implications.

Except that when we get to macroeconomics, a lot of people don't practice this common sense.

Historians, politicians, bureaucrats, pundits, and many economists tell us that the stock market is like the thermometer. Fair enough. What evidence do the provide to support that position? Well ... because it seems to have been right once in 1929. It's been right other times (I can confirm that), but if you think about it, it's really weird that you can't actually name any of those other times. You probably don't know anyone who can either.

Then the news media trumpets what our stock market thermometer is doing ... every day, and more often if you'd like to pay attention. Investors may have reason to pay attention to that, but there are also people around who've bought into following the stock market and have been waiting a long time to get their 1929 signal. How on Earth are so many people so

certain that stock market behavior caused the 2007-9 recession? Heck, economists aren't even sure it

contributed to causing the recession, and we have all the data and computers and know-how and stuff. It's so bad that if we admit we looked and didn't find much, the public tunes us out.

And almost no one admits that business cycles might be inherently difficult to predict, that the data is uncertain, and that it's a big world with a lot of transactions to worry about. It's messy! Every family has stories about how hard it is to figure their kids out, how they tested out different approaches and got contradictory results, and society accepts that. Few people accept that business cycles are hard to figure out, or that our tests might not work very well.

But we plug away at it. Macroeconomic outcomes are important for personal well-being. We can measure them fairly well with real GDP. We can forecast that with some accuracy. But the economy changes from well to sick and back once in a while. It's even pretty easy to forecast real GDP if we assume it will stay expanding, or stay contracting if we're in a recession ... it's the timing of the switches from the one to the other that are tough to figure out. And we're testing all the time, whether it's explicit or implicit, but the tests aren't very good.

In some sense, getting false positives and false negatives is a good sign. It means we care enough to be trying to figure things out. And we can't get false ones at all without running the tests and getting some true results too. Caregivers are doing their job when they take a kid's temperature once in a while, and we cut them some slack about how they interpret the results. We need to take the same approach to macroeconomics.