Most of the time, the new research discussed in this blog is not timed to match what we’re doing in class. I got lucky this time.

Also, while there is a paper behind this post, I’ve been unable to find a free copy of it. So I’m going mostly on the basis of the discussion of this in this Marginal Revolution post.

******************************************************

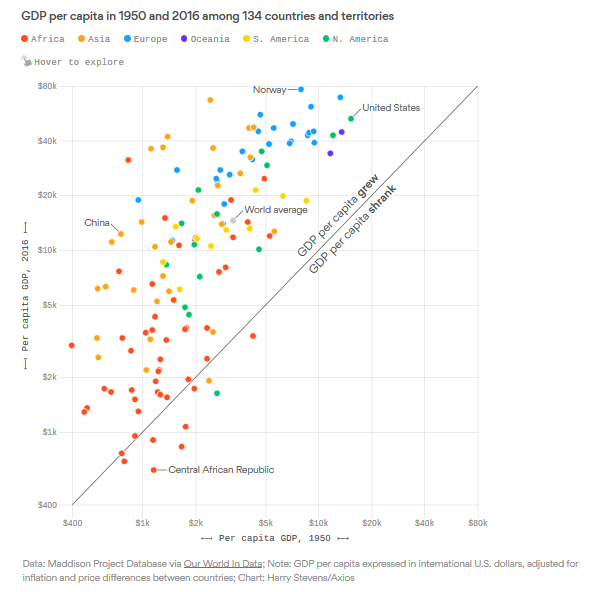

In class we’ve been talking about geographic correlation. This is the fact that we all live near each other to improve our level of well-being, and it seems to work.

I’m not a big fan of cities, but the message there is that urbanization is telling us something really important. I emphasized in class that countries collect data, and tell us how important they are, but the critical macroeconomic action seems like it might be at a lower level.

In contrast, we have a problem in the U.S. and in many other countries: people in cities know they have a good thing going, and don’t want any more people moving into their city and ruining it. The acronym often used for this is NIMBY: short for Not In My Back Yard. In the U.S. NIMBY-ism often takes the form of real estate zoning, which restricts the density of new construction, and the uses to which it can be put. For example, it’s very difficult to build a new home in coastal California due to zoning restrictions, and this places constant upward pressure on the prices of existing homes in that region.

In this new research, they build a theoretical model, and use it to explore counterfactuals. That’s a good college level word: it means they look at “what if” scenarios.† In particular, they look at what would happen if people could just move to, say, New York City, without current residents of New York putting up legal/cultural/social/political barriers to keep newcomers out.

Here’s how Tyler Cowen summarizes some of this:

1. If you restricted New York City and Los Angeles to the size of Chicago, 18.9 million people would be displaced and per capita rural income would fall by 3.6%, due to diminishing returns to labor in less heavily populated areas.

2. The average reduction in real income per person, from this thought experiment, would be 3.4%. You will note that NIMBY policies are in fact running a version of this policy, albeit at different margins and with a different default status quo point.

3. If you were to force America’s 11 largest cities to be no larger than Miami, real income per American would fall by 7.9%.

4. If planning regulations were lifted entirely, NYC would reach about 40 million people, Philadelphia 38 million (that’s a lot of objectionable sports fans!), and Boston just shy of 30 million (ditto).

5. Output per person, under that scenario, would rise in NYC by 5.7% and by 13.3% in Boston. That said, under this same scenario incumbent New Yorkers would see net real consumption losses of 13%, whereas for Boston the incumbent losses are only about 1.1%.

6. The big winners are the new entrants. On average, real income would rise by 25.7%.

7. Alternatively, in their model, rather than laissez-faire, if America’s three most productive cities relaxed their planning regulations to the same level as the median U.S. city, real per capita income would rise by about 8.2%.

[emphasis is mine, not original]

As a closer, let me note that this problem is worse in most other countries (what makes America so rich is the large number of pretty big cities, not the few huge ones). For example, consider Seoul, where the population of the metropolitan area is half of the whole country … how many of you can even name another South Korean city.

† As students advance to higher levels, where modeling is pushed out to them more often, the common complaint is — Why do we have to do all this math? The answer is to make better counterfactuals.