There's been suggestions that the U.S. could temporarily solve its debt ceiling problem by having the Treasury mint a coin worth a trillion dollars, and then depositing that coin at the Federal Reserve.

If it sounds stupid ... it probably is.

***

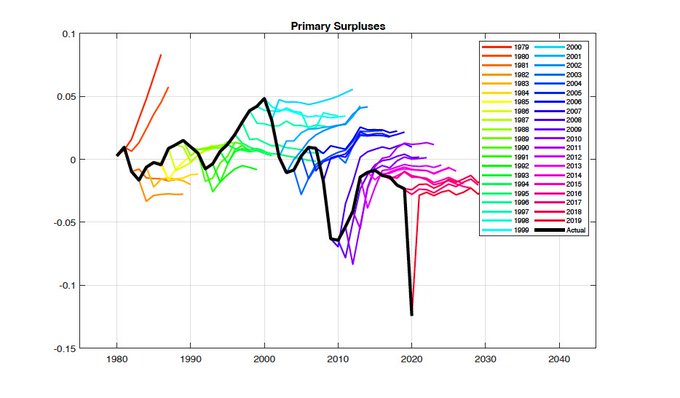

Review: the debt ceiling is an issue because Congressional decisions about spending are not connected to decisions about revenue, the difference is financed by net borrowing (the deficit), the accumulation of which is the debt (or national debt), and there's a ceiling on that that isn't connected to the other two decisions.

A more subtle issue is that Congress doesn't usually allocate exact amounts to things its spending on (particularly entitlements). Instead, it passes laws with stipulations to do some thing and worry about how much later on. It's worse with taxes, where Congress sets rates, but you and I (and the IRS) determine the amount (called the tax base) that the rate is applied to. So on spending side its mostly guesstimates and on the revenue side its all guesstimates.

***

No one is worried about the debt ceiling who is also willing to just cut spending (or raise taxes). Of course, it would be helpful not to have the guesstimates to make this all easier, but it's a doable thing.

A problem with that is that much spending is on "autopilot". Entitlements are like that: they go up whether we want them to or not. Revenue is also on autopilot (most of us agree in advance on how much to have them withhold from our paychecks). But then the problem goes back to the previous section: autopilot is convenient but it doesn't fix the fact that they aren't tied together.

***

The long-term issue with the debt ceiling is that Congress is undisciplined with its spending and revenue decisions. The debt ceiling is the outlet for this.

The short-term issue is that if we hit the debt ceiling, the Executive branch can only use tax revenue to fund spending that's already been promised. The practical solution is then to just make the payments that are required (interest on the debt and entitlements) and put everything else on hold. There's enough leeway that this will actually work. But it's not desirable.

And this might actually make the Executive branch look like it's the problem. It's not, but that doesn't mean they won't scheme to avoid that.

***

Enter the trillion dollar coin. This is an idea put forth by Jack Balkin in 2011. More on Balkin later. That suggestion (related to a debt ceiling issue then) never gained traction.

Representative Rashida Tlaib revived the idea in 2020, and formally introduced a bill into the House to do this. More on Tlaib later.

Our currency is not backed by anything. It has its value because 1) the government prints it on there, and 2) people like you and I believe that and act upon it.

Balkin's idea is that if you say the coin is worth $1,000,000,000,000 (fulfilling # 1), then # 2 will follow.

(Parenthetically, Balkin also made the claim that they couldn't print $1,000,000,000,000 in currency and do the same thing because there's a statutory limit on printing currency. I've been doing macroeconomics for 40 years and I've never heard of such a thing. It's possible what he means is that you can't print a bill that large. That's true, and the statute is in place to make money laundering more problematic for those interested in doing it. Even so, the only reason you couldn't print up a large number of smaller bills is that it would be inconvenient to move them around).

Anyway, to make # 2 work, Balkin would have the coin deposited at the Fed, and then would withdraw smaller amounts to make payments.

(If that seems silly, because you could just print the currency ... you're not wrong).

Another interpretation of what Balkin meant is that while the Executive branch mints coins and currency, statutorily it can't put them directly into circulation. Instead, it does have to run them through the Federal Reserve, which then puts them in circulation.

Later the idea has been covered by the journalist Izabella Kaminska (ungated version here). And this year the big pushers of the idea are Rohan Gray and Nathan Tankus. More on Kaminska, Gray, and Tankus later.

***

There's a lot of detail there. Let's cut to the checks and balances. The distinction between the Legislative and Executive on this is that the former does the general stuff, and the latter does the specific stuff. So the Legislative branch can't micromanage, and the Executive branch can't dictate overall totals.

But the Legislative branch has also put a check and balance on itself, by making the spending action subject to both ex ante and ex post approval. The trillion dollar coin is a scheme for the Executive branch to get around the ex post part.

***

At this point, we get to something most of you understand: economics is hard.

And I'm not really trying to be Chauvinist here; non-economists can do economics, but you'd really like the economists doing this stuff. Except ...

- Balkin is a law professor.

- Tlaib is a Representative, with a law degree, who never really practiced law.

- Gray is ... you guessed it ... a law professor.

- Tankus is a ... well ... I guess you'd call him an "internet authority". And college dropout.

As budding economists, you're going to have to get used to this. Let's just say, in an analogous situation in public accounting, these people would all be jailed.

Note that Kaminska is a journalist whose just reporting what she finds out. And some of her views are sound, others just offbeat (not getting the satire in the tweet from Zerohedge she linked to) or silly (the meme included, which is way too literal).

***

What's being proposed here is essentially ... quantitative easing ... a policy the Federal Reserve has already pursued for about 15 years.

In quantitative easing, the Fed buys illiquid assets (often Treasury bonds) and pays for them with liquid assets (usually reserves), which can then be readily converted into money.

Most of the time, they'd buy those bonds from whoever has them. But the Federal government owns trillions of dollars of bonds issued by its own Treasury. The trillion dollar coin is like making sure those bonds are first in line for purchase. (Of course, the Fed and the government could do this any old time: the Fed would make an offer for bonds low enough that no one would take it, and the government could volunteer to take the offer).

This all makes the trillion dollar coin ... a prop ... for people who don't understand how things already work.

Why do they need a prop? Really they don't, but my guess is that it would obscure that this is equivalent to taking bad offers to sell on what you own on behalf of the American people.

But somehow the prop is really important. Gray has even suggested that the military could be used to force an uncooperative Fed to accept the trillion dollar coin. Yikes.

***

All of this misses a couple of subtle points about economics.

An easy one is that money is not the same thing as currency, coins, and reserves. In my principles classes, I like to modify money with "inside", and then group the other three as "outside money". Almost all money is inside money, because the financial system isn't just banks, or the Fed ... it's all of us. And inside money is a reflection of the interactions of all of us in this system. The people who like the idea of the trillion dollar coin are hung up on the importance of the much smaller outside money. If we've learned anything with the unconventional monetary policy of the last 15 years, it's that the financial system is very inelastic with regard to changes in outside money.

The harder point is that we really don't buy things with money. We buy stuff with stuff, and use money as a convenience to do that more readily. All of us sell stuff and get money in return. So money is a memory of that stuff. Then we take the money to go buy other stuff (from someone doing the opposite of what we're doing). The government is doing the same thing. The stuff it's selling is the promise of programs that attempt to fulfill some objectives. Our taxes and loans are what it gets in return. Then it uses those to make payments on those programs. The key point is that you buy stuff with stuff, and the government buys stuff with stuff, and we both use money as a convenience: stuff in, stuff out, money in the middle. The non sequitur committed by proponents of the trillion dollar coin is that if have more money, then you can get out more stuff than goes in.

Some mathematicians, when they see something that can't work, use a really cutting phrase to describe: "that's not even wrong".