In the class quodlibet, JH asked about macroeconomic myths and folktales. Many of those are untrue. Understanding what goes on with oil requires unlearning a whole bunch of things you probably are sure are true.

***

There's always stuff on the news about oil prices. But price of what exactly?

Almost always those are prices for crude oil. This week it's up to $130/barrel, but there are expectations that it might go as high as $150-200/barrel within the next few weeks.

What's crude oil? It's the black to tan liquidy stuff that comes out of the ground. It's found all over the world, but is concentrated in about 20 major spots, and a lot of minor ones: Texas, Alaska, North Dakota, California, Pennsylvania, even Utah; and in countries like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, Iraq, Iran, Libya, Russia, Venezuela, Mexico, the UK, Norway, Romania, Indonesia, Ecuador, Gabon, and so on.

What's a barrel? Well, that's pretty obvious. It's also a measurement: 42 gallons.

Got questions about what some of these things are? McKinsey has a glossary that covers many of them.

Crude oil is heavy. A barrel weighs about 300 pounds, so it's a notional estimate. No one actually has barrels of the stuff around except for waste oil in shops.

Now do the math. Oil was about $40/barrel for years, went up to about $80/barrel due to COVID-19 lockdowns, and is now up even further. Those correspond to about $1, $2, and $3 per gallon.

This site breaks down retail gas prices in California each week. You can see that right now the cost of crude is about 55% of the retail price. But, if you scroll back a few weeks, you'll notice that all the other items add a consistent $2.30 to $2.35 to the cost of the crude. So all the ups and downs are coming from the cost of crude, and not from what refiners and shippers do.

***

Crude oil has different qualities. Each well is different, but it's a commodity: traders buy it in volume, so they tend to view all oil from one region as just about the same. Kind of like saying California oranges (which look better), and having people know those are different from Florida oranges (which taste better).

The grades do get finer than this, but what you need to know is light and sweet (up and to the left on the chart). Crude oil is either light or heavy, depending on whether it's less dense or more dense. Crude is also sweet or sour, depending on how much refining it takes to get the nastier stuff separated out. Lighter and sweeter is better, and therefore more expensive.

***

Most crude is priced relative to widely available types that everyone uses for comparison. These are Brent (from the UK side of the North Sea) and WTI which is short for West Texas Intermediate. Their prices are close, and not surprisingly Brent is used a lot in Europe and WTI in America. The prices you see are usually quotes for these. Other crudes are usually quoted with a negative price, indicating that they are being sold at, say, $5 less per barrel than WTI.

Russia has lighter sweeter crude coming from the Ural Mountains in the left center of the country. This is usually loaded on tankers in the Baltic. It sells for a small discount off of Brent. After the invasion it was being offered for $11 off of Brent and no one would take it.

Russia also has newer oil wells in eastern Siberia that produce a heavy sour oil. And they have a lot around the Caspian Sea, which I think is also light and sweet, but I'm not sure.

***

Getting oil is not cheap. It costs between $30 and $90 per barrel to get it out of the ground. There's harder to get oil out there, but no one produces it unless the price gets high enough.

People think oil is always a profitable business (it's like you're own printing press for money). Wrong. Unlearn that.

Oil companies are big. You all took micro. When you see an industry where all the firms are big ... it's because they either get big or they die in bankruptcy. Small oil producers are not very profitable because there's economies of scale in this industry. This isn't wrong or bad or unfair, it just is.

Because the firms have to be big, they can make a lot of profits. But they do not have a high rate of profit, which is what everyone who's had more than 6 weeks of economics or finance classes cares about. You can invest in oil companies, but they aren't a great investment. Apple is a good investment, and it's bigger than most oil companies, but somehow it has a good rep. Go figure.

A more appropriate view of oil producers is that they're like Walmart. They make a tiny little bit on each part of a high volume operation. People like Senator Warren, who claim otherwise, are either morons ... or they think voters are morons. You decide.

***

So why do we think of countries when we think of oil?

Here we combine both ignorance, and the law.

We've covered the ignorance. People think you drill and then buy a yacht. If it worked that way you'd be planning on staring an oil company after graduation. But it doesn't. Amongst the most ignorant are politicians and bureaucrats in countries that are trying to get bigger and richer (the country gets the first and the politician gets the second). Oil works best for them if they 1) have a lot of it, and 2) don't have very many citizens to worry about. This is why we associate oil riches with desert Arab countries. But if you don't have a lot of oil, you stay poor, as in Egypt, and even if you have a lot of it you won't get rich if you try to support too many people off of it, as in Nigeria. I suspect a lot of rulers in these countries start out with the idea that the oil is free, and then find out the hard way that it's expensive to get out of the ground and sell.

And the law is, that in most places, while you may own land, you only own the surface. You don't own what's underneath. The U.S. is one of the exceptions to this: if you drill for oil on your land, it's yours. But most countries aren't like that: in them, the government claims to own all the mineral wealth under the ground. That's really convenient if there's oil down there. (For what it's worth, in the western U.S. the states own all the water under the surface, just like oil in other countries).

So, for a lot of countries, there are oil "companies", but they're only nominally independent of the government. So Mexico has Pemex: a state monopoly. Russia has a few oil companies, but they are controlled by oligarchs. A lot of countries also lease the oil they own to those big American and European oil companies: Exxon, Chevron, BP, Shell, and so on.

Countries with oil can earn a lot of foreign exchange by selling their crude on international markets. This is where Russia gets most of its money. I remarked earlier in the semester that Putin can cause trouble now because he's flush with FX from recent increases in oil prices, and new fields in Siberia coming online. But he's making all that money on volume, not margins.

***

But crude is only the first part of the story.

Have you heard that America is dependent on foreign oil? Don't be stupid. Unlearn that one too.

Crude oil is close to useless. It used to just lay around the surface of the earth in pools. It still does in the La Brea Tar Pits, and elsewhere. And people used it for very little, except waterproofing.

Over the years refining developed. There's not a ton of money in this either, but there's more than in crude.

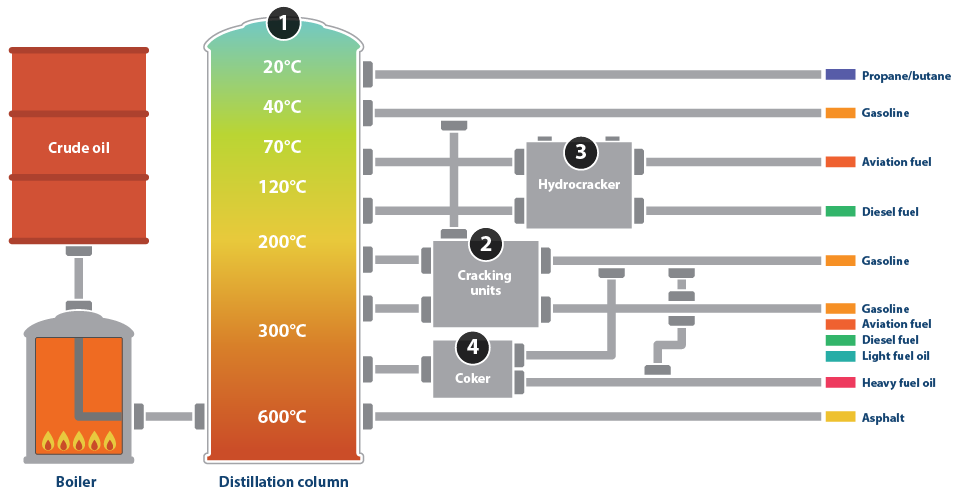

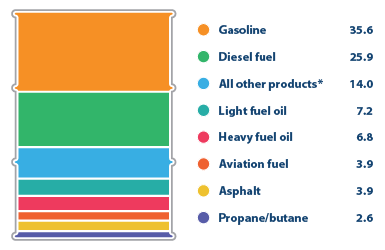

Crude oil is like an old car that's worth more in parts than as a vehicle. Refining does two things: 1) separate out the oil into different products by density, and 2) chemically alter some of them to turn them into more desirable products. This page has details on what comes out of crude oil (for Utah kids familiar with ranching ... it's similar to the idea that no part of a cow goes to waste).

The lightest parts of crude oil is stuff like the butane in cigarette lighters. "Light" is the name used here, but what they really mean is least dense. Gasoline is also pretty light. Gasoline isn't that special: there's just a lot of it in crude oil, it flows well, it vaporizes easily, so it got adopted for engines (invent the engine for the new-ish fuel that's useful and easy to get, right?). It's not a coincidence that oil drilling, refining, and gas engines all came online one right after the other in the last half of the 19th century.

The heavier parts of crude oil get refined into other stuff: diesel, jet fuel, motor oil, heating oil, gasoil, bunker fuel (for ships), tar, asphalt, precursors for plastics, and even stuff like vaseline (that's a brand name for the product petroleum jelly). The goal is to find a buyer for all of it: think about, there's aren't big pools of leftover oil residue all over the place.

Coming out of the refinery, a barrel of gasoline is light enough to float on water. A barrel of tar, on the other hand, weighs most of the 300 pounds that the barrel of crude did.

If the crude oil is sour, it contains more impurities. This makes refining more expensive. Nasty smelling but fairly harmless sulfur is the big problem here.

Light sweet crude oil sells for more than heavy sour crude oil because you get more valuable stuff out of it more easily. But refiners can use both.

The trick is that a refinery is designed and geared for the sort of oil that's it's likely to be used for. They can be repurposed, but it requires shutting them down for weeks or months to retool.

So, America is supposedly "dependent on foreign crude oil". Yeah ... right. The correct story is that we have a lot of refineries because we're smart and rich. In fact, there's no problem in having more refineries than you have oil. So while America has always been a big producer of crude oil, and has been the biggest over the last 10 years, it's an even bigger refiner. We do all of ours, plus a lot of other countries because it's a good idea. Duh.

Oh ... and people excessively focus on how much crude oil the U.S. imports. They ignore the even larger amount of refined products we export. It's almost like they're trying to suppress the real story, isn't it?

This site has some accessible details about the economics of refining. This page is a little more involved, but has some cute econometrics. Both sites discuss the 3-2-1 crack spread, which is a simple convention for figuring out if refiners are making more or less money than they were before.

***

We're getting towards the end now. Gas used to be about $3/gallon, and a dollar of that was from crude. Now the crude has gone up to $2-3 per gallon, adding $1-2 to the price of gallon of gas. The other $2 in between is the costs of refining, transporting, taxes, and profits.

Transporting oil is fairly cheap (transportation usually is), but remember that this is a high volume low margin business, so any transportation cost is an issue.

Storing oil is also fairly dangerous (and it's getting stored for a while as it's being transported, right?).

But doing either for oil is safer than doing it for gasoline, the major component.

So the economically efficient way to do things is to 1) refine what you need between the well and the city, and 2) ship the rest of it to big refineries somewhere else. For example, most gas bought in Utah comes from the refineries near Woods Cross, that get most of their oil from around Vernal and Wyoming.

Thus, the prices on the spot market for oil associated with countries is for shipments of what they are producing in excess of local needs. It gets shipped to refineries, that then ship finished products to regions that don't have any wells or refineries.

Even so, oil of a certain grade is usually shipped to refineries set up to handle that grade, which are located as close as is feasible. For example, Texas has refineries for light and sweet crude from Texas, but it also has them for heavy and sour crude from Mexico and Venezuela. Part of the reason that the oil industry wanted the Keystone XL pipeline was to bring more crude oil from Canada (really heavy and sour) to refineries set up for that in Texas, which didn't have much business because Venezuela's incompetent government killed their oil drilling industry over the last 25 years. Tons of people understand this, but the just-so story of pipeline=bad was what dominated the news. Few people realize that the alternative is not no oil being shipped across the country to Texas, but rather oil going in tanker trucks and rail cars through peoples' neighborhoods. Oops. Face palm.

***

Oh ... one last tidbit. Oil tankers are big because they have to be efficient to reduce costs because it's a low margin industry. So most oil tankers won't fit through the Suez or Panama canals.

Thus middle-eastern oil often goes to Asia, Russian oil to Europe, and so on.

For America, this means that oil imported to the east coast often comes from the UK and Norway, but not Russia because it's a bit further away. But Russian oil goes to, say, Germany, because it's just as close as the UK and Norway.

Russia also sends oil out through the Black Sea to countries around the Mediterranean. And they send oil from eastern Siberia to China, South Korea, and Japan. A lot of that goes by pipeline rather than ship.

And, maybe you're seeing this coming: also to the west coast of the U.S., and especially Hawaii. The left coast also gets a lot of oil from Ecuador and Indonesia.

***

Because of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, some countries want to shut off Russia's oil exports. Here's some of the issues.

Low margins on the production side mean that there is rarely a lot of spare capacity in the oil industry. It's all going all the time, or it's shut down. But shutting down wells isn't easy: they're pretty much ruined and have to be redrilled. This means that supply is inelastic.

It's worse because refineries are set up for the oil that's nearby. So can Europeans get oil from elsewhere? Sure. Can they get the oil that won't require shutting down and retooling their refineries? That's tougher. Yes, but at a price. And when they stop buying Russian oil, it gets picked up by the Indians because (at a discount) it's competitive with oil from the Middle East. And we're worried about what the Chinese will do because they get their Russian oil in a pipeline, which is easier to hide.

It's worse because our demand for oil is also inelastic. This is why they worry about Russia's oil and gas being cut off during what's left of the European winter.

Combine inelastic supply and inelastic demand and you get a lot of variability in prices without much variability in quantity. This is why prices at the gas pump change so much in normal times, much less this year.

Now, Russia is a big exporter of oil, but no country is huge. The figures I saw is that Russia export 8% of the world's oil, and comprises 3% of U.S. imports of oil. But it will be the west coast and especially Hawaii that will bear the brunt of this week's ban on oil imports from Russia. All prices will go up everywhere, but it will be worse to the west of us. Utah will have less of an effect because there aren't many pipelines bringing oil in from the coast: we have our own little insulated oil region in the Great Basin.

***

Biden is being made to look the fool this week around some of these issues.

He called Saudi Arabia and the UAE and they refused to take his calls! The goal here was to ask them to ramp up production. This is a dumb political move that only dumb political people could think would work (again, a few weeks in a micro class would help them out). The issue is, what exactly did they think Saudi Arabia and the UAE were doing before? Not ramping up as fast as they could?? Oil prices have been increasing for a while. All these countries were hurt by low prices in 2020-21. They already are ramping up as fast as they can to take advantage of better prices. Asking them to do more is just for show, and kind of insulting to boot.

(In addition, Saudi Arabia and the UAE see the Biden administration as favoring Iran over them. Do you think they're going to let that slide when he comes begging for more production?).

Then there's the Biden administrations overtures to Venezuela. This can be presented to the gullible media as "let's stop hurting the country with the leftist government"). But it's worse than that. If they had not stopped the Keystone XL pipeline, there would have been less need for this since Gulf Coast refiners would have already been going full speed ahead. So this also is tied up in politics and the politicians are hoping you and I won't notice that they're doing politics again. Whatever.

I have some charts and figures to attach to this post, but it's taken me so long to write, that I'll be adding them before and after class. I'll note them with updates down here.

***

3/12 Update: Preliminary reports show that imports of Russian oil were already down to zero in the last week of February. This is before Biden's ban, and was accomplished by decentralized decision-making in the private sector.

3/14 Update: Here's that tweet about the price of gas now versus the zombie movie I Am Legend. (with pictures) ;-)